|

| The Crusades |

The Saga

Commencing at the end of the 11th century, the Crusades would become somewhat episodic, running until the 15th century. Including the Reconquista, they would extend seven centuries, approximately the same duration as the conflict between the Roman and Persian empires (which had ended just four centuries earlier).There were a total of nine formal Crusades, or armed expeditions to the Holy Land. In total, there would be 19 military incursions between Europe and the Muslim Caliphates. The Eastern Empire would have numerous territorial wars with Islam, and Constantinople (today’s Istanbul) would eventually fall to the Muslims of the Ottoman Empire in 1453.

Byzantium would have limited participation in the crusades to the Holy Land. However, being Christian, certainly did not weigh in the Eastern Empire’s favor after Pope Urban II declared intolerance towards Islam and indiscriminate bloodletting by the crusades began.

The First Crusade

Historians usually consider the Paupers’ Crusade and the Princes’ Crusade as a combined representation of the First Crusade. However, since the Paupers’ Crusade (sometimes called the People’s Crusade) had only about two dozen trained knights under the leadership of Walter Sans Avoir, there could be little doubt the far more militarized Prince's Crusade became the first serious armed excursion. This followed about three months behind Peter the Hermit and Walter San Avoir’s outing of untrained rabble, numbering in excess of 40,000. Although 3,000 "paupers" are said to have survived the final slaughter in Anatolia, at the hands of the Seljuq Muslims, there exists no record of any members of the Paupers’ Crusade returning home to Europe, other than Peter the Hermit. The somewhat clairvoyant Peter had an uncanny knack of being required elsewhere whenever a major incursion was imminent. |

| Peter the Hermit with Knights |

With the departure of the Paupers’ Crusade, Pope Urban had at a minimum, succeeded in getting a good number of Europe’s poor and undernourished population out the door. No doubt, a good number of depraved were amongst them. However, for Pope Urban to provide a serious response to Emperor Alexios request for military aid, he was obligated to muster something resembling a military force. In assembling armies of armed knights, who were otherwise roaming and pillaging the countryside, he would also take a considerable bite out of Europe’s high crime rate.

This latter force is known today as the “Princes’ Crusade”. It would begin departure from various locations beginning in August of 1096, four months after the Paupers’ Crusade, and arriving two months after the slaughter of that expedition.

Departure

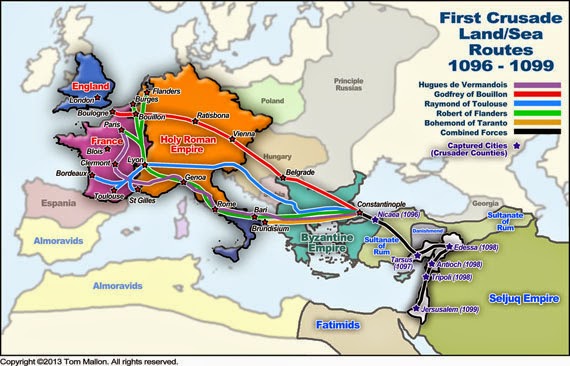

The five armies comprising the second expedition would be lead by Godfrey of Bouillon, Raymond di Saint-Giles, of Toulouse, Robert of Flanders, Bohémond of Taranto and Hugues I of Vermandois. Hugues of Vermandois army would be the first to depart, arriving before the others in Constantinople in November of 1096. Hugues would take the southern route through Italy ahead of Bohémond (see map), losing some of his troops crossing the Adriatic. All five armies would pick up troops and materials along the way. Godfrey, Raymond and Robert would depart from various locations in France and pass through Germany in August of 1096. Bohémond would push off from the boot of Italy, to cross the Adriatic, in October. The ones that did not meet up on the trail would eventually combine forces upon arrival in Constantinople between November of 1096 and April of 1097.

|

| Click to Enlarge |

Enforced State Religion

To the Christian mind of the 11th century, the inhabitants of the earth were divided into three groups, Christians who followed Church doctrine, heretics, who questioned it, and infidels who subscribed to different beliefs. Such was the hold the institution of the Church had on its subjects. Heretics, or fallen Christians, had been routinely tortured and condemned to death since the establishment of ecclesiastical law centuries earlier. |

| Medieval Inverted Hanging of Jews |

By the 11th century, the Jew had become firmly established as a Christ-killer (Jewish Deicide). This was somewhat ironic, for had the Jews of Jesus’ time actually killed him, the capital punishments of Judaism were limited to stoning, burning, beheading and strangulation (hanging). However, Christ was crucified, a punishment reserved for the crime of sedition against the state of Rome. Therefore, it was somewhat incongruous that Christians, fixated upon the cross, would conveniently overlook this detail.

|

| Godfrey of Bouillon |

Godfrey’s point is clear, using the war of the cross to sway conscience with gold for motivation, more Jews would die. The Frank towns of Mainz and Cologne would pay Godfrey 500 silver marks to move on. Others were less fortunate. Upon news of their approach in the Rheinland, entire families were reported to commit suicide rather than be captured, tortured and raped or in other ways forced to convert. Such was the fear instilled by the armies purported to represent the gentle Christ.

Arrival

The Emperor’s Doorstep

Since the Crusades had been the response to Emperor Alexios’ request to Pope Urban II for military assistance after the fall of Anatolia, the princes heading the five armies naturally assumed they would be meeting up with Byzantine forces upon their arrival in Constantinople. Instead, the emperor decided, once again, to have the forces hold up outside the walls of Constantinople and negotiated with just the leading knights. |

| Arrival at Constantinople |

Compromise

Emperor Alexios had prohibited Peter the Hermit’s mob from entering Constantinople for pretty much the same reasons a captain would work to prevent rats from boarding a ship. However, the knights were an entirely different matter. Not only had Pope Urban sent Alexios the earlier unwanted mob of mostly untrained, unprovisioned civilians, he had also succeeded in enlisted armies of a considerably larger size than the emperor would have imagined, armies large enough to overthrow the emperor’s own somewhat susceptible Byzantine government.As though to confirm these suspicions, there was the pretentious letter from Hugues de Vermandois. Moreover, the formidable Bohémond of Taranto had (along with his father, Robert Guiscard) been in a territorial war with the Byzantine Empire over disputed Italian and Eastern European provinces for half a decade. Certainly, any competent head of state would have become mistrustful of the Pope’s motives.

|

| Alexios I Komnenos in Conference |

Circumstantial Cheerleaders

|

| Peter the Hermit with Knights |

It’s unknown exactly how many of the earlier expedition made it back from Anatolia. Only about 3,000 survived the Turkish massacre. Far fewer managed to make passage back across the strait. These civilian ranks would grow with the injured as well as prostitutes that would eventually journey eastward to make their own fortunes.

Pre-Siege Assembly

|

| The Emperor and Knights |

Divided Goals

The War of the Cross was slowly developing into a war of betrayal between the Eastern and Western Christian hemispheres. A questionable gift of aid from Pope Urban II had resulted in conflicting interests. The clever Emperor Alexios would turn things to his favor for a time but once the Crusaders experienced success and gathered a foothold, Christian would work against Christian, with both sides sometimes employing the use of Muslim aid to counterbalance the other’s purpose.In retrospect, the gift aid from the Pope had resulted is suspicion and limited support by Emperor Alexios. The Crusaders, who had originally set out for the Holy Land, would eventually be tied down in a three-way territorial struggle.

As the Crusaders would distance themselves from the Eastern Empire with miles and broken pledges, their resolve to beat a path to Jerusalem would continue to grow. Nicaea would prove to be a military classroom for the knights. The larger than life Bohémond of Taranto with his former experience of fighting the Byzantines would adapt to deal with the military tactics of the his new Muslim. Along with Richard the Lionheart (Third Crusade), Bohémond would become one of the most formidable warriors and tacticians of the Crusades, a thorn in the side to both Muslim and Byzantine.

Commentary

Blessed are the Meek

Had Emperor Alexios been more trusting and the Crusaders proven to be more trustworty, the outcome of the Crusades may have unfolded towards a far different conclusion. Based upon known events, the restoration of Anatolia with the formidable aid of the Crusaders was well within the realm of possibility. Subsequently, a foothold in the Holy Land and an alliance with the Muslims would have likely been reached. |

| Anatolia |

|

| Sermon on the Mount |

Ironically, seven and a half centuries earlier, Constantine had employed the cross to unite and strengthen east and west forces. Now its sudden appearance upon the knight’s tunic would only further divide the two halves of the former empire, as the Crusades would work to establish a new competing Eastern Kingdom centered in Jerusalem.

Click here for 16) Siege of Jerusalem

|

|

Got Feedback?

Comments? Questions? Corrections? Any feedback at all? Just click on the comments box at the bottom of this page and enter your thoughts. All comments are welcome.

Santuario de Guadalupe, the oil painting by Tom Mallon. This 42" x 22" canvas is the latest addition to the Santa Fe Portrait Series. The Santuario is the oldest shrine to Our Lady of Guadalupe in the US.

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE

Shostakovich and Cultural Snobbery, Could anyone survive Stalin's Purges, compose a large body, write for himself and the masses while producing constantly great work?

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE

Tom Mallon's website "MallonArt". This website will provide you with links to all his paintings, drawings and other artwork portfolios, including the ongoing series entitled the Santa Fe Portrait.

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE

No comments:

Post a Comment